Bernd T. Matthias: a few stories of my academic grandfather

Bernd T. Matthias was my academic grandfather as he was thesis advisor my thesis advisor, Robert N Shelton. I was in the same room as Matthias only a few times and never had so much as a conversation with him. Even so he had a strong influence on me, and I'm grateful for that. I thought I would put down some of the stories I remember about him. He was a remarkable scientist with encyclopedic knowledge of the properties of materials and uncanny scientific instincts, which I hope to illustrate here. For a more complete biography see this link:

https://nap.nationalacademies.org/read/5406/chapter/14

My first indirect encounter with Matthias

I joined Shelton's solid state physics group in Ames, IA in 1978 to study superconductivity and magnetism. Bob (I always called him Bob and he never corrected me though everyone else called him Robert) had just arrived in Ames and was building a lab from empty rooms with concrete floors. I felt I needed a lot of hands on experience and saw the required building of equipment as an opportunity.

About the first real project Bob put me on involved the family of ternary Rare Earth Rhodium Borides typified by YRh4B4. Before Matthias physicists had studied superconductivity in nearly every element, and nearly every binary compound consisting of any combination of two elements. The prevailing view was that compounds of three elements (called ternary compounds) would be chemically more complex but exhibit no new physics compared to the simpler materials. Matthias had shown that view was wrong, so as I was getting started the new area of ternary superconductivity was just getting going.

Matthias had identified these new termry Borides which were just beginning to get serious attention because they exhibited competition between superconductivity and magnetism which, in some cases, and previously been thought impossible.

He did something I'd never heard of. He'd identify a promising family of compounds, then he'd publish some short paper in an obscure journal. A paper designed not to draw attention but merely to stake a prior claim. I'm pretty sure he did this for the ternary Borides though when I looked just now I couldn't find the obscure citation. Perhaps I misremember this particular case. The idea seemed odd to me at the time, not quite in keeping with the open spiri of science. But over the years I saw the wisdom of this as many times the review process ends up revealing your discovery before you're own claim is well established.it was the early days of my education.

Superconductivity and the elections per atom

An example of his astonishing intuition, and also his self confidence, appears in this paper, just older than me:

Empirical Relation between Superconductivity and the Number of Valence Electrons per Atom

B. T. Matthias

Phys. Rev. 97, 74 – Published 1 January 1955

https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRev.97.74

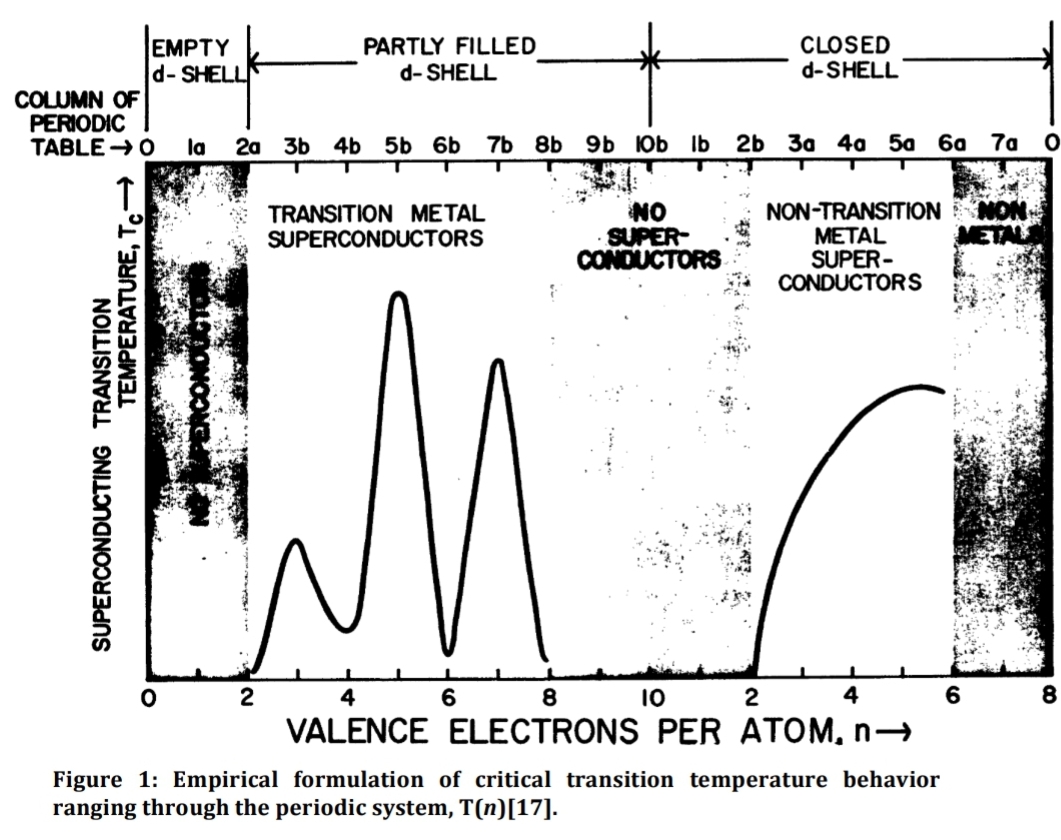

I can't find a copy of the original figure in that paper (and I'm to cheap to spend $35 for a copy right now) but in it he plots perhaps 12 data points and draws by hand two peaks in the superconducting transition temperature vs the number of valence electrons per atom (na). Here's a much later schematic of the plot he made, showing peaks at 5 and 7 na:

In the years following his 1955 paper hundreds of compounds filled in the two peaks. He was was auditious, and usually right.

There are no red superconductors

I heard this story more than once, always told as if it was true. I can't verify it but it's a wonderful story worth telling either way.

A theorist at UC San Diego (possibly Lu Jue Sham, a prominent solid state theorist at San Diego at the time) had just concluded a long and very difficult calculation of the superconducting transition temperature for a chemical compound that had not yet been found to exist. But he was very excited to test his theory so he asked Matthias for help. Matthias confirmed the compound had never been previously reported but he thought it very likely could be prepared.

Matthias picked a good grad student and sent him to the theorist. The student and theorist worked for six months and the student confirmed by X-rays and density and such that it really was the compound the theorist wanted and the two men went excitedly to Matthias to arrange for a low temperature measurement to see if it was indeed superconducting or not.

Matthias took one look at the sample and declared "that's not a superconductor. It's red and there are no red superconductors."

The theorist and student were devastated, but Matthias was right: it wasn't a superconductor.

Matthias knew materials. Metals are typically sliver, or even copper colored, or even gray. Not always shiney. And very rarely they may have a slightly bluish tint. The electrons that move around in metals influence the color, you see. But red results from defects in insulators, which are never superconductors. Only decades later did the high temperature superconductors emerge, which are often much closer to insulators than these classical metals. And they were a great surprise, in part because Matthias's rules were so widely accepted that it was pretty heretical to find the new oxide based superconductors.

Listen carefully to what Matthias says is true but ignore his explanations completely

On my own thesis committee I had a theorist named Sam Liu. Same was a character in his own right. A first rate theorist, with a strong and serious personality. Sam gave me this advice about Matthias, who knew wall.

Sam told me to listen very carefully to Matthias. If Matthias tells you something is a known fact, he's always right. If Matthias makes a prediction, also listen very carefully because here too he is nearly always right.

But when Matthias gives an explanation as to why this or that is so, you should probably ignore him completely because his explanations are almost always wrong.

Sam, of course, was exaggerating. But his point was taken. Such was the intuition and encyclopedic knowledge of the world of materials.

Matthias and Ferroelecticity

In my years after leaving Ames I never again worked on superconductivity. But wherever I went I kept running into other academic descendants of Bernd Matthias and we all shared at least something of a common language, one my say a common scientific culture. The man left quite a legacy that way.

I'd be remise without adding one more story. Bernd studied ferroelectric materials in his thesis and afterwards in the 1940s. Ferroelecticity has some analogy to ferromagnetism. In ferromagnetism, a material contains atoms that have magnetic spins which more or less all line up pointing in the same direction. So a chunk of a ferromagnetic material acts as a magnet and can stick to your refrigerator, as well as do many other interesting and useful things.

A ferroelectric material is in a rough sense similar but in stead of being a permanent magnet it has a permanent electric field. The underlying physics is completely different, or course, and at the time in the 1940s there were only about a half dozen or so known materials with ferroelectric properties. It was considered quite rare indeed.

Matthias in just a few years identified many, many more ferroelectric materials and deloped guidelines on how to look for more of them. Right from the beginning the man showed deep insights on the properties of solids. I really only appreciated his role in ferroelectrics when I was asked to write an encyclopedia article on the Ferroelecticity.

Those are some of the stories I recall about Bernd Matthias.